Tropical Milkweed, Good or Bad?

I know what you are thinking when you read this title. "Milkweeds are good for Monarch butterflies!" "Pollinators of all kinds feed off of Tropical Milkweeds." That, for the most part, is true. However, there is much debate between policymakers and the scientific communities that research these butterflies.

To begin this discussion, ask yourself, in the beautiful great plains of the United States, why are we planting tropical Milkweed? The short answer to this question is that the plant looks very pretty when blooming. There is no denying the appeal to the eye when seeing the bright orange and red blooms which can appear on the plant in as little as four months. Seeing the endangered monarch caterpillars feeding on this plant is also an added benefit. Knowing all this, the plant markets itself in the eyes of a retail grower.

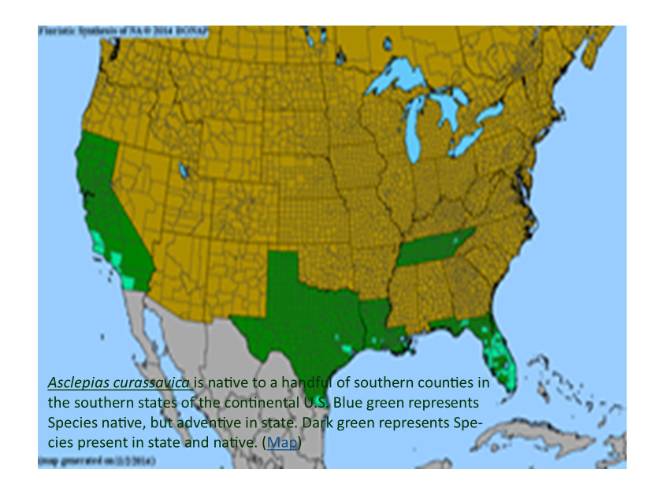

This information, at face value, means very little. Plenty of beneficial pollinators and host plants in our garden are non-native plants. Queen Anne's lace is an example of this in regards to black swallow-tail butterflies. There are, however, two things about Asclepias curassavica that should be known about its physiology. First, tropical milkweed blooms during the entire growing season, right up to the freeze. This differs from the perennial milkweeds that lose all their leaves, flowers, and seeds during the fall and are almost unrecognizable by the first freeze. There's much debate about whether this confuses the monarchs in continuing their migration south to Mexico. It is assumed that monarchs wouldn't continue to Mexico if there were still food (nectar and leaves) for them and their offspring. Scientists who study these insects quickly point out that migration is more influenced by photoperiod and temperatures rather than food availability.

The second thing the public should be aware of is a protozoan parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, or OE. This parasite is found on all milkweeds. However, it doesn't survive in the foliage during the winter. In more temperate environments than ours here in northeast KS, Asclepias curassavica can perennialize and not go dormant, creating a higher concentration of OE in the leaves. This is the case in southern Texas, California, Louisiana, and Florida, where freezing temperatures rarely happen. California's Department of Food and Agriculture reclassified tropical Milkweed in 2022 to a Class B Noxious Weed, allowing counties to ban this plant's sale. Marin, Contra Costa, San Mateo, and Ventura counties did ban the sale of the plant.

Infection of OE can happen in three ways. A caterpillar can eat from a plant containing the parasite's spores within the plant hairs; a male can pass it on to a female during mating, and an infected female can pass it to her offspring when she lays eggs. Once infected by this parasite, monarch caterpillars grow and weigh less. Other symptoms can include difficulty emerging from the pupal stage, decreased wingspan, wing deformities, wings more prone to tear, and increased larval mortality. Adults infected with OE also have a reduced likelihood of completing the migration.

OE is a problem to be aware of, especially if you live in any of the southern states where freezing temperatures are rarely seen. Although the symptoms look awful, they are not the most significant contributing factors to declining monarch numbers. The largest factor is Climate Change. California's Department of Food and Agriculture felt the need to act because of winter mating behavior they noticed in recent decades. Some arguments say that without these milkweeds on the coast, winter mating would not occur. With climate change being a certainty now, this behavior could also be the species trying to adapt to continue to survive.

Combating climate change seems like a daunting task. So, what about another factor that we can control? Habitat loss. Have you ever seen one of the sides of our highways? Whenever I drive anywhere in Kansas, I see countless host plants growing in ditches. Then, my heart breaks when I see it get completely mowed down. Kansas Department of Transportation (KDOT) says they spend 6.7 million dollars on mowing the sides of highways because of safety, vegetation control, improved drainage, and aesthetic reasons. But other places do it differently. Driving on the interstates of Iowa, you can see where mowers deliberately don't mow down colonies of Milkweed. This practice must be adopted on a large scale across the country in order to preserve native pollinators.

Of course, another contribution to the decline of all insects is our chemical use in the landscape. Since the post-WWII period, this country has used all sorts of pesticides and herbicides. Even a handful had to be taken off the market because of how dangerous they turned out to be or the lack of care we were using when applying these chemicals. Yet any department store that sells pesticides and herbicides with no licensing or training needs to buy them. Companies specializing in pesticides and herbicides only need one employee with a license to supervise, not licensed holders. The abundance of spraying each year has contributed to the decline of insects worldwide.

There is more than one factor contributing to the decline of the monarch butterfly. It's not just OE on tropical Milkweed, chemical applications in the landscape, human-caused climate change, or even habitat destruction. The decline of monarchs can be attributed to a combination of all these things, creating extreme survival stress on the species and forcing them to adapt in ways we may not understand for years to come.

The purpose of this article is not to advocate for the ban on all tropical milkweeds. More information is needed to inform the public about what discussions are being had about this popular plant nationwide. However, if given the

choice to plant tropical Milkweed or a native variety, please pick a native one, three, or five. Providing a diverse array of milkweeds isn't just beneficial to caterpillars who feed on them but also adds to the biodiversity of your landscape. There are at least 20 species of Asclepias native to Kansas. Most of them will grow and thrive in the Kansas City area. Another native host plant prevalent in the area is honeyvine Milkweed.

Alternative Milkweed Varieties to Consider

As mentioned before, Kansas has at least 20 native species of Asclepias. Unfortunately, not all can be found at retail garden shops. This is for several reasons, including seed availability, seed viability, difficulties germinating seed, and performance in production and gardens. However, many can be found on the side of highways, pastures, and woodland edges. (photos to assist with ID are below the descriptive paragraphs)

Common Milkweed(Asclepias syriaca) is very common on roadsides. It can grow to above 5 feet and is drought-tolerant. The large, thick leaf has a spikey seed pod. The seeds readily germinate in the landscape and are considered aggressive and "weedy."

Purple Milkweed (Asclepias purpurascens) This Milkweed offers a vibrant red-purple color in a shady spot. Grows to three feet tall. Soil needs consistent, even moisture. They are considered difficult to cultivate. Seeds do not readily germinate and may be difficult to source.

Sullivant's Milkweed (Asclepias sullivantii) is Similar to common Milkweed but has a pink mid-vein, is less aggressive, and has a smooth seed pod. It has very fragrant flowers that bloom in summer and is drought-tolerant. It can hybridize with common Milkweed, removing some of its distinctive characteristics.

Showy Milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) is similar to common Milkweed, but the "hood" of the flower is longer. Flowers usually appear in summer. It is more commonly found in the western half of Kansas. Less aggressive than common Milkweed. Drought tolerant.

Swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) is tall and has white and pink blooms that appear in mid-summer. Its leaves are similar to those of tropical Milkweed. Swamp milkweed likes consistent moisture. It is great for pond edges and is very popular in retail shops.

Spider milkweed (Asclepias virus) (also referred to as Antelope Horn milkweed) is a short-growing milkweed with green blooms and deep rose-white centers. It is drought-tolerant but doesn't do well in thick vegetation. It blooms in late spring and early summer.

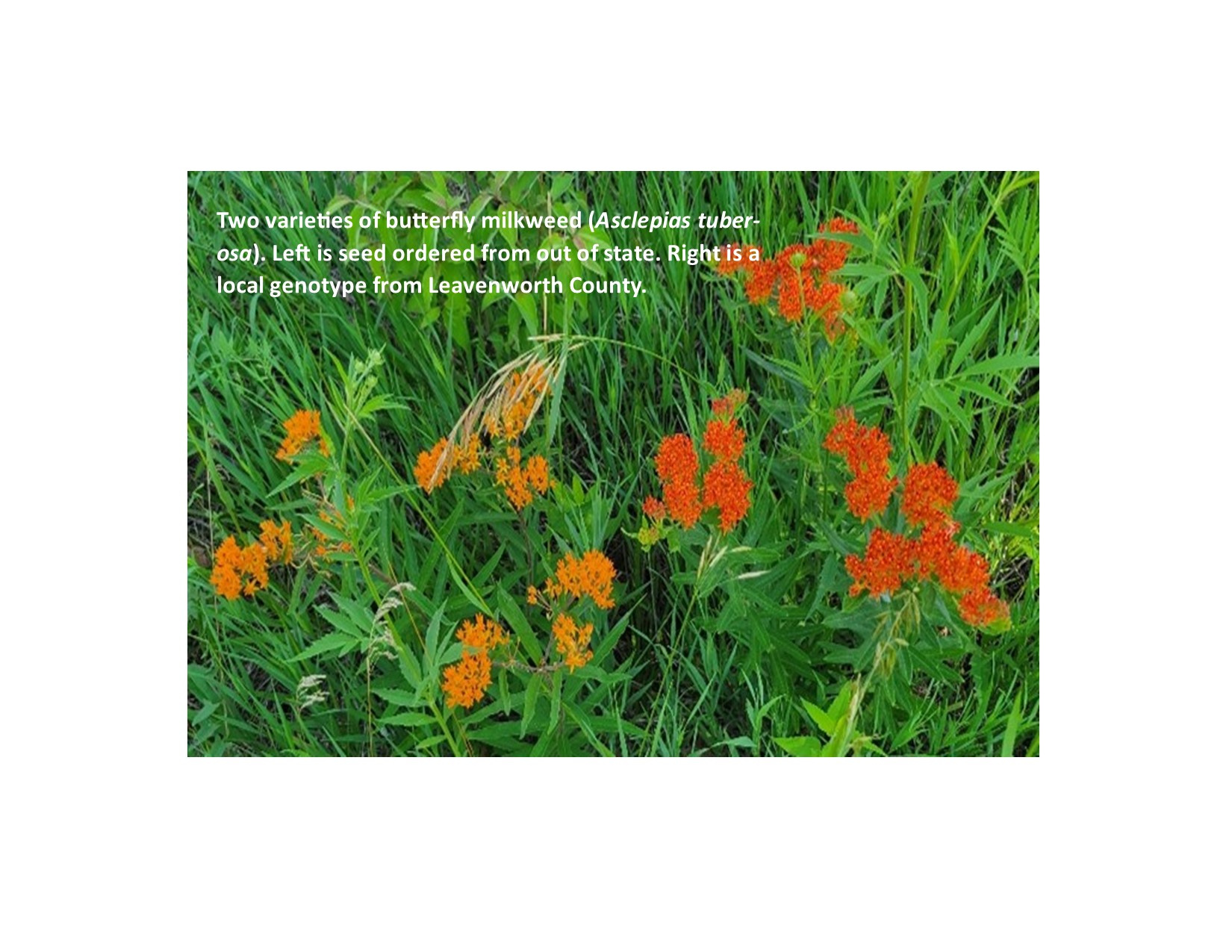

Butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) is a low-growing milkweed with showy orange blooms. It was the Perennial Plant Association Perennial Plant of the Year in 2017. It is very popular in commercial production. Blooms in late spring and early summer. Flowers can be orange, orange-red, and yellow. Large tuberous taproot. Drought tolerant. Seeds readily germinate in commercial production.

Whorled Milkweed (Asclepias verticillate) This is a low-growing type of Milkweed that does well in full sun and dry soils. Leaves offer a fine texture. Flowers appear in small, white clusters in the summertime. Will spread from underground rhizomes as well as germinate from seed

Honey Milkweed Vine (Cynanchum leave) is not a true milkweed; however, monarch caterpillars will eat it down to an unrecognizable string. Pollinators of all kinds love the flowers. This is a very aggressive grower in any soil type and growing conditions. It can fully cover shrubs and small trees. Leaves are heart-shaped with small clusters of white flowers. Pulling off any seed pods on the vine is advisable, as you do not want this to spread to other parts of your home garden.

To experience Monarch tagging and learn more:

If you want to learn more about the migration of monarch butterflies, consider attending Hasta Luego Monarchs at the Olathe Pollinator Prairie on September 28, 2024, from 9 am to 1 pm.

Markis Hill, Horticulture Turf and Ornamentals Agent, 2024